Abstract- Father Sky

Native American communities established complex systems of learning that incorporated multifaceted skills utilizing all human senses as they relate to the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual—individually and communally—with society and nature. The boarding school process of assimilation stripped away generations of this way of learning from 1819 to 1934, creating an insurmountable wave of trauma arising out of education for several generations to follow. However, despite generations of trauma causing mistrust of institutionalized education systems, Native communities see success with education attainment and repaired relationships with the institutionalized education system through tribally based, culturally conscious institutions and curricula. Financial education for Native communities must be in balance with Native culture to be accessible to community members.

Prayer, Song, and Introduction- East/Sweetgrass/Beginning

Banganan Anami’aa | Serenity Prayer

Anishinaabemowin/English

Chi manidoo, daga wiidookawishin | Creator help me

Weweni ji naanaagadawendamaan ji odaapinamaan | to accept

Iniw ge-gashkitoosiwaan ji aanjisidooyaan | those things that I cannot change

Ji de-apiichide’eyaan ji aanjisidooyaan | the power to change

Ge-gashkitooyaan | those things that I can

Ji de-apiichi-nibwaakaayaan | and the wisdom

Ji gidendamaan ono / to know the difference.1

Nyaa nindinendam | Oh I am thinking

Mekawiyaanin | I am reminded

Endanakiiyaan | Of my homeland

Waasawekamig | A faraway place

Endanakiiyaan | My homeland

Nidaanisens e | My little daughter

Nigwizisens e |My little son

Ishe naganagwaa | I leave them far behind

Waasawekamig | A faraway place

Endanakiiyaan | My homeland

Zhigwa gosha wiin | Now

Beshowad e we | It is near

Ninzhike we ya | I am alone

Ishe izhayaan | As I go

Endanakiiyaan | My homeland

Endanakiiyaan | My homeland

Ninzhike we ya | I am alone

Ishe giiweyaan | I am going home

Nyaa nigashkendam | Oh I am sad

Endanakiiyaan | My homeland.2

Gegemnado Creator, thank you for the space to share the story of our ancestors and how the effects of boarding schools have impacted several generations interactions with institutionalized learning environments. Please bless the path of healing from this trauma and hold our relatives in sacred care on their journey. Please also extend forgiveness, though it may be difficult, to those that have caused such harm to our people and our knowing that forgiveness is on the road to healing.

Chii Miigwetch, Many Thanks.

This is one piece of a seven-part series unpacking the complexities surrounding financial education for Native American communities, utilizing interviews from prominent Native American individuals across the financial education sector and accessible literature. Together, these seven pieces create a snapshot of this landscape. As financial knowledge coexists with access to financial products and services in the National Endowment for Financial Education’s Personal Finance Ecosystem, this article discusses the very brief history of boarding schools for Native American children, the traumas faced by many (but not all), and the deviation from indigenous models of learning to the institutionalized model of learning. One of the core concepts within the National Endowment for Financial Education’s Personal Financial Ecosystem is “Financial Knowledge and Access.” Financial knowledge, defined within this ecosystem, is “the objective mastery of financial definition, terms, and concepts” and access and inclusion, “refers to participation in financial society, which NEFE defines as the opportunity and awareness to take action and exercise choice within financial markets, the financial services industry, and all aspects of financial life.” However, if the knowledge keepers and transference of knowledge are embedded in an institutionalized model of education, access can be restricted through historical trauma with the system.

History- South/Cedar/Growth

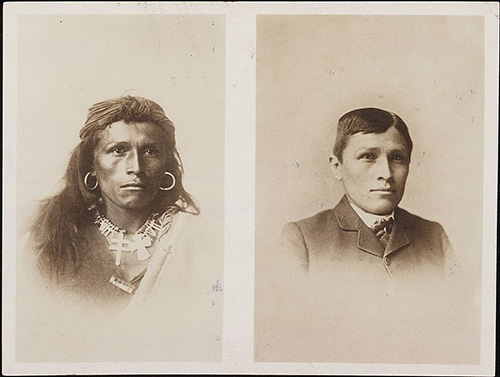

In the “History and Foundation of American Indian Education” by Stan Juneau, traditional Native education is through the transference of knowledge by imitation, oral tradition, and hands-on training. Foundational to indigenous teaching and learning is learning how to learn, enveloping methodologies that incorporate listening, observing, intuiting, and experiencing all the human senses. These educational systems address learning as it relates to the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual needs of the tribal members within the Tribal society. In addition, indigenous models of education are delivered individually. With this approach, individuals have the choice to partake in educational activities and on their own terms.

“Indigenous pedagogy is a lived experience where intuition and the inner journey of reflection inform a learner’s process of coming to know deeply. Learning about the inner process of balancing the heart, mind, intuition, and body through being in the moment and journeying to the inner space of reflection and self-knowing are fundamental to exuding positive perspectives outwards to relationships with others and for the understanding of and appreciation of Indigenous perspectives”

- Sharla Mskokii Peltier “The Child is Capable: Anishinaabe Pedagogy of Land and Community”3

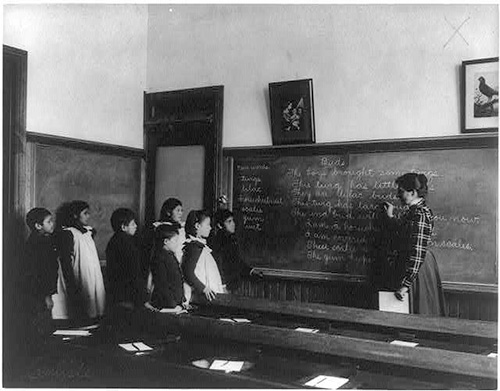

On March 3, 1819, The Civilization Fund Act was passed by the United States Congress. This act approved funding for the instruction of Native American children to be taught reading, writing, and arithmetic.5 Much of this funding was allocated to white missionaries to establish schools in and around Native communities. In 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was established and would oversee the funding of this program.6 The first federally-run boarding school was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1879.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man”

– Captain R. H. Pratt, National Conference of Charities and Corrections 1892

In his speech, that so famously coined the phrase “kill the Indian, save the man”, Captain R. H. Pratt outlines the divisiveness of the governmental policies that had systematically eradicated Native nations, culture and people. He points out that the boarding schools brought on financial growth to the surrounding white communities, stating, “Nothing could be better calculated to secure failure in uplifting the Indians and to prolong an unnecessary and expensive management…. Every appropriation, every movement, must be based on its probable pecuniary advantage to the white race.” His speech was designed to support his Carlisle Indian Industrial Boarding School, and in doing so, portrays the perception of Native Americans by white Americans at that time, which was that they possessed, “savage language, superstition, and habit.”

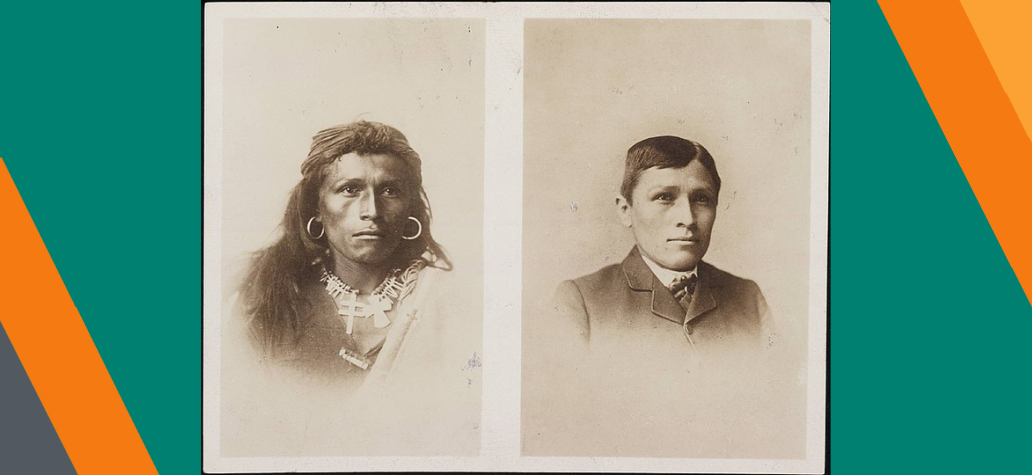

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School had become a model for federal Indian boarding schools across the country. this model to fully assimilate Native American youth, they were forced to attend the school for three to five years. Pratt also started a summer program to keep youth over the summer, to completely remove Native children from their language, clothing, culture and beliefs. 8 Their doors finally closed in 1918 and the buildings were transferred back to the United States Army as a rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers.

The Meriam Report of 1928 brought to light the inadequacies of the boarding schools and the violation of child labor laws, encouraging lower enrollment rates.9 By the 1930s, most federal Indian boarding schools had been closed.

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Act of 1975 was a turning point in education for Native communities, creating schools that have culturally relevant curriculum and local Native leadership.

Similarly, the Education Amendments Act of 1978 provided financial support to tribally-operated schools and encouraged local hiring of teachers and staff. In a restructure in 2006, the Office of Indian Education Programs was renamed to the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) . The mission of the BIE is, “to provide quality education opportunities from early childhood through life in accordance with a tribe’s needs for cultural and economic well-being. Further, the BIE is to manifest consideration of the whole person by taking into account the spiritual mental, physical, and cultural aspects of the individual within his or her family and tribal or village context.”

In June 2021, the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative was developed with leadership from Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to investigate the federal Indian boarding school policies. The investigation found that the boarding school system consisted of 408 federal schools across 37 states, identifying marked or unmarked burial sites at approximately 53 schools as of 2023. The Bureau of Indian Affairs states that the purpose of the boarding schools was to culturally assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children by forcibly removing them from their families, discouraging use of language, religion and cultural beliefs.

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report Volume 1 utilizes federal documentation to highlight the experiences within the boarding schools. The days were structured with little to no down time for the children, the quarters were cramped with multiple children to a bed, the curricula involved vocational training that would violate child labor laws of the time. Because of the poor conditions and close quarters, disease spread quickly through the schools.

The Administration for Native Americans in the Administration for Children and Families in the United States Department of Health and Human Services addresses the negative impacts of the boarding school era that transcend generations from adverse childhood experiences. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), as defined by the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years), or aspects of the child’s environment that undermine their sense of safety, stability and bonding. These experiences are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance issues. The CDC also notes that these experiences can negatively impact education. The CDC states, “Some children may face further exposure to toxic stress from historical and ongoing traumas due to systemic racism or the impacts of poverty resulting from limited educational and economic opportunities.”

Discussion- West/Tobacco/Maintenance

“And what happens to Indigenous people is that their educations and their cultures are destroyed, their worldviews become subsumed into this notion of the social contract, consent to the governed state of nature, it's all the same thing. And so boarding schools were incredibly effective at that. They were not insidious, they were overt, physically, emotionally brutalizing. They would destroy physically injured children in order to prevent them from talking in their language, from looking like Indian people, from acting like Indian people, but far more importantly from thinking like Indian people,” states Chief Justice Matthew Fletcher (Anishinaabe).

He also described the American system imposing the exact indoctrination ideology through society, schools, and governance. Through this indoctrination, individuals lose connection to culture and community values, and focus on the individual through wealth accumulation.11

“But the brokenness of what boarding schools in the Western education model did to our communities, I feel we're still suffering those effects in terms of drug abuse, alcoholism, just regular abuse and living in some of us perpetual poverty. The interaction with the Western model of civilization, that still doesn't work, nor will it,” says Chrystel Cornelius (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), CEO of Oweesta Corporation.12

Lance Morgan (Ho-Chunk), CEO of Ho-Chunk, Inc., echoed this sentiment stating that the experience had triggered alcoholism, drug abuse, sexual abuse, and many other negative coping mechanisms that have cascaded into several generations.13 These cycles stem from ACEs and take a conscious effort to break.

In the interviews conducted for this research study, many shared stories of their relations’ interactions with the boarding schools, all having been stripped of language and culture. Because of these traumatic experiences, Christopher Cote (Anishinaabe), business development impact manager at First American Capital Corporation, describes that a fear and skepticism of pursuing education was developed and passed down generationally. The individuals who had experienced abuse at the hands of educators were hesitant to encourage their children to go to institutionalized education facilities. He says that four generations later, this generation is now seeing encouragement to obtain higher education and successes through tribal colleges and universities.14

“I think we're seeing a great insurgence of so many young people who want to know their language, they want to go back to ceremony and we're providing that on so many levels and that gives me hope for the seven generations,” Cornelius states.15

Similarly, Dawn LeBeau (Lakota) mentions that there is a resurgence in remembering and sharing indigenous practices. The next generations are going to have to find a balance between an industrialized education and indigenous, which includes language and culture.16

“We're seeing that colonial way of being within an education system was very ‘this is how you do it’. ‘You do it our way’, and they stripped our people of so many things. But now what we're seeing is that communities are doing it their own way and becoming more in tune with who they are as a tribe and to be able to get beyond the atrocities and hopefully in a way that is healthy,” states Onna LeBeau (Omaha), director of the Office of Indian Economic Development.17

Jaime Gloshay (Dine, Apache, Kiowa) mentioned the positive impact of her son going through the Native American Community Academy in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “I’ve witnessed my son go through that school and really thrive and be comfortable in leaning into his indigenous identity and getting prepared for a college education.” There is a level of protection around his identity and confidence that gives, “more agency and autonomy in his pathway as he moves forward.” She also mentions that this is a time for reimagining frameworks and systems of education.18

Morgan states, “I believe we are on the verge of creating a virtuous cycle of high expectation and opportunity where generations of our people can live in an environment where success is an expectation, not a dream”. In the Ho-Chunk Village in Nebraska, they are seeing positive outcomes from the tribal high school and tribal college in the form of increased graduation rates.19

Unfortunately, the road to success in the United States does not end once higher education is obtained. Gloshay notes that some generations viewed institutionalized education as the “end-all, be-all” of assimilation; the key to closing the racial wealth gap. However, once she had earned an undergraduate and graduate degree, there were larger systemic issues of white supremacy in work culture, patriarchy in leadership, and power in multiple levels of tribal governments and corporate worlds.20

Wisdom- North/Sage/Conclusion

In conclusion, not only were the boarding school education models very different from indigenous models of education, but they were also a vehicle for generational trauma, instilling fear of institutionalized learning for Native children who survived the experience. There is a resurgence of cultural revitalization and a desired balance with institutionalized forms of education. Native communities have seen success in culturally integrated forms of education. There is a desire to integrate indigenous ways of knowing and indigenous ways of educating; developing curriculum designed for the transference of knowledge on the mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional level; and incorporating all human senses. Because financial education is intrinsically embedded with white American culture, it is important to consider implementing a curriculum that is culturally accessible. The forthcoming article—“Successes of Grassroots, Native-led Financial Education”—will discuss methods for adapting financial education for indigenous models of resource management.

Disclaimer- Mother Earth

There are 574 Federally Recognized tribes and hundreds of unrecognized tribes in the United States, each with a unique colonization story that has influenced their community members’ and descendants’ interactions with the mainstream financial system. These articles are intended to explain a generalized Native experience and support a journey of positive change in relation to Native American, Hawaiian Native, and Alaskan Native communities.

About the Weaver- The Spirit Within

Boozhoo, Migizi ‘ikwe Nindigoo. Stephanie Cote Nindizhinikaaz. Grand Traverse Band Odawa minwaa Ojibwe Nindibendaagoz. Maengun Nidodem.

Hello, spirits know me as Eagle woman. I am called Stephanie Cote. I am from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. I am from the Wolf clan.

Stephanie Cote descends from a lineage of basket weavers. Honoring her ancestry, these articles are woven from common Native knowledge, accessible online articles, and the wisdom imparted by Native peers and elders to support hypotheses developed from the intersectionality of Native American experience and financial education. She is Odawa and Potawatomi from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians from Northern Michigan and a Senior Program Officer at Oweesta Corporation leading the Financial Education and Asset Building Department.

1 page 58, Ambe, Ojibwemodaa Endaayang! Come On, Let’s Talk Ojibwe at Home! By Jessie Clark (Mookwewidamokwe) and Rick Gresczyk (Gwayakogaabo) © 1998, Eagle Works, Mpls, MN

2 https://ojibwe.net/songs/traditional/nindinendam-thinking/

3 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.689445/full#B7

4 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tom_Torlino_Navajo_before_and_after_circa_1882.jpg

5 https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/3/STATUTE-3-Pg516b.pdf

6 https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/mar/03

7 https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3a27579/

8 https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-carlisle-indian-industrial-school-assimilation-with-education-after-the-indian-wars-teaching-with-historic-places.htm

9 https://narf.org/nill/documents/merriam/n_meriam_chapter9_part1_education.pdf

10 https://www.loc.gov/item/2007662291

11 Interview with Matthew Fletcher; Date May 11, 2023

12 Interview with Chrystel Cornelius; Date July 12, 2023

13 Interview with Lance Morgan; Date May 24, 2023

14 Interview with Christopher Cote; Date July 13, 2023

15 Interview with Chrystel Cornelius; Date July 12, 2023

16 Interview with Dawn LeBeau; Date July 14, 2023

17 Interview with Onna LeBeau; Date May 15, 2023

18 Interview with Jaime Gloshay; Date July 20, 2023

19 Interview with Lance Morgan; Date May 24, 2023

20 Interview with Jaime Gloshay; Date July 20, 2023