Abstract- Father Sky

Before colonization, Native American communities relied on nature and the surrounding environment to provide sustenance for survival. As indicated in the previous article “The Origin Story: Manifest Destiny's Creation of Economic Deserts and the Devastation of the Subsistence Economy,” Native American communities had been relocated or given meager portions of their traditional homelands. This relocation resulted in an inability to harvest adequate foods from the land for survival. For several generations and in hundreds of communities, rationing and commodity food programs combined to increase the physiological impacts of poor-quality foods, thus increasing health disparities among Native Americans. Similarly, these foods have influenced the behavioral economic patterns that keep Native Americans in a negative cycle of physical illness and disease as well as financial insecurity from medical costs. These financial behaviors, conscious or unconscious, affect individual financial well-being and are a consideration when developing responsive financial education.

Prayer, Song, and Introduction- East/Sweetgrass/Beginning

“Gizhawenimimin Gichidibenjiged

We are blessed by you Lord;

(Anishinaabemowin/English)

ezhi-aanikoobidooyan gakina gegoo.

You who connects all being.

Gizhawenimimin Giizis

We are blessed by you Sun

ezhi-mashkawizi’iyaang.

You give us light and strength.

Gizhawenimimin Dibiki-giizis

We are blessed by you Moon

gikinoo’amawiyaang zaagaasidiyaang.

you teach us the importance of reflection.

Gizhawenimimin Mashkiigi

We are blessed by you Land and Water

ezhi-ditibiziyan wenji-bimaadiziyaang.

your circulation supports our living.

Apii zhawenimiyaang, zhawenimangidwaa.

As we are blessed, we bless others.

Apii zaagi’iyaang, zaagi’angidwaa.i

As we are loved, we love others.

Apii noojimo’iyaang, noojimo’angidwaa.

As we are healed, we heal others.

Apii inawenimigooyan, inawenindiyaang.

As we are related to you, we are related to one another.

Naadamawishinaam daga noongom

Help us all now

Nagamotawishinaam daga noongom

Sing to us all now

Nanaa’ishinaam daga noongom

Repair us all now

Nana’isanishinaam daga Gichidibenjiged.

Bring peace to all our souls O Lord.

Apii ziigwan ozhiga’angwaa ininatigoog

When it is spring we tap the maples

Apii ziigwan iskigamizigeyaang

When it is spring we sugar bush

Ininatigaboo minwaagamin

Maple sap tastes good

Ziinzibaakwad minopagwad

Sugar tastes good

Zhiiwaagamizigan giminwendaamin

Maple syrup we like it

Gitchi-manadoo,

Creator,

Thank you for the bounty that flourishes and nourishes your people. Please guide us in a healthy way on our journey on this sacred planet Mother Earth. Thank you, Mother Earth, Shkaakaamikwe, for providing for us in every way, for our very existence would not be without you. We are grateful for each day and the blessings given. Chii Miigwetch, Many Thanks.

This is one piece of a seven-part series unpacking the complexities surrounding financial education, including financial well-being, for Native American communities, utilizing interviews from prominent Native American individuals across the financial education sector and accessible literature. Together, these seven pieces create a snapshot of this landscape.

The National Endowment for Financial Education's Personal Finance Ecosystem identifies the factors that influence financial well-being, which includes the core concept Financial Actions and Outcomes Cycle. This cycle is, “a feedback loop comprised of the individual’s mindset and available choices, followed by the decisions made and actions taken by the individual as well as the resulting outcomes and the impacts of any external shocks (i.e., unexpected events).” This article unpacks how a diet of commodity foods and historical rations influence financial behaviors, which lead to a cycle of negative medical issues and poor-quality food choices.

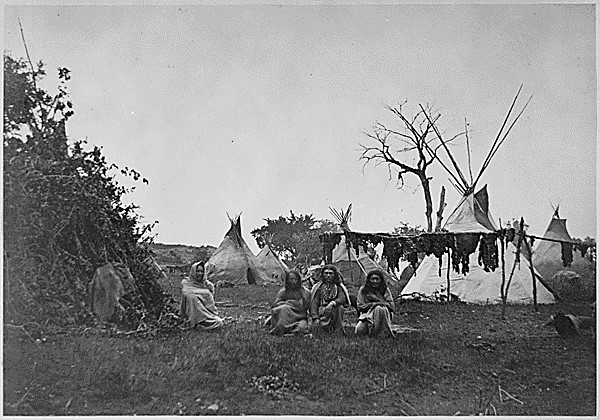

History - South/Cedar/Growth

Native American communities survived and thrived on cultivating the land for nourishment. “Before colonization of North America, our ancestors were healthy and strong,” shares Nico Albert in “Food, Culture, and Storytelling.” Native American diets were designed for the people of their respective regions. Subsistence living contributes to overall well-being, through physical activity, a healthy diet, and psychological wellness. Native American harvesting practices also provide ecological stewardship of the land through sustainable and regenerative hunting and gathering. This knowledge is tied to the specific ancestral territories of each individual tribe, band, or clan. “It's our responsibility to do the best we can to give back to the living beings that are all around us,” states Hope Flanagan (Seneca) in the article “Elder Voices: Wisdom about Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems from the Holders of Knowledge.” “For example, you don't ever take a plant without putting down an offering first. Mother Earth is a living being that has gifted us food, water, breaths, everything.”

“The Origin Story: Manifest Destiny’s Creation of Economic Deserts and the Devastation of the Subsistence Economy” shared the history of relocation of Native American communities to smaller portions of traditional lands or to new lands, sometimes hundreds of miles away. This forced removal limited the space for traditional practices of hunting and gathering or placed communities into foreign territories to cultivate the new land they were inhabiting with lack of traditional knowledge of that land. Between 1778 and 1871, tribes had engaged in over 400 treaties with the United States government, often determining hunting, fishing and farming rights of tribal members, many of which stated the U.S. government promise to secure adequate articles of subsistence. This was the beginning of government interaction with the food systems of Native American communities. As articulated in the report, “Feeding Ourselves,” the rations were often processed foods of lower nutritional value, unlike the historical diet of people indigenous to the United States. Moreover, rations were commonly rancid or rotten upon delivery.

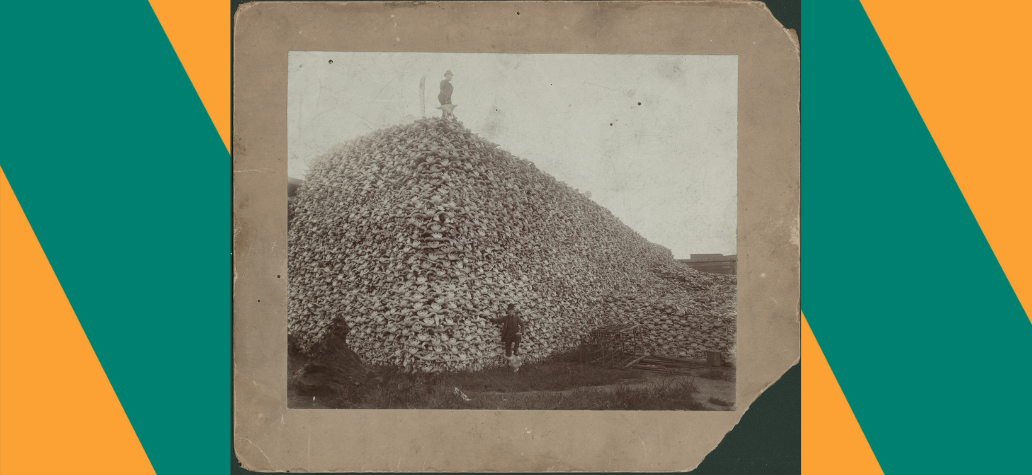

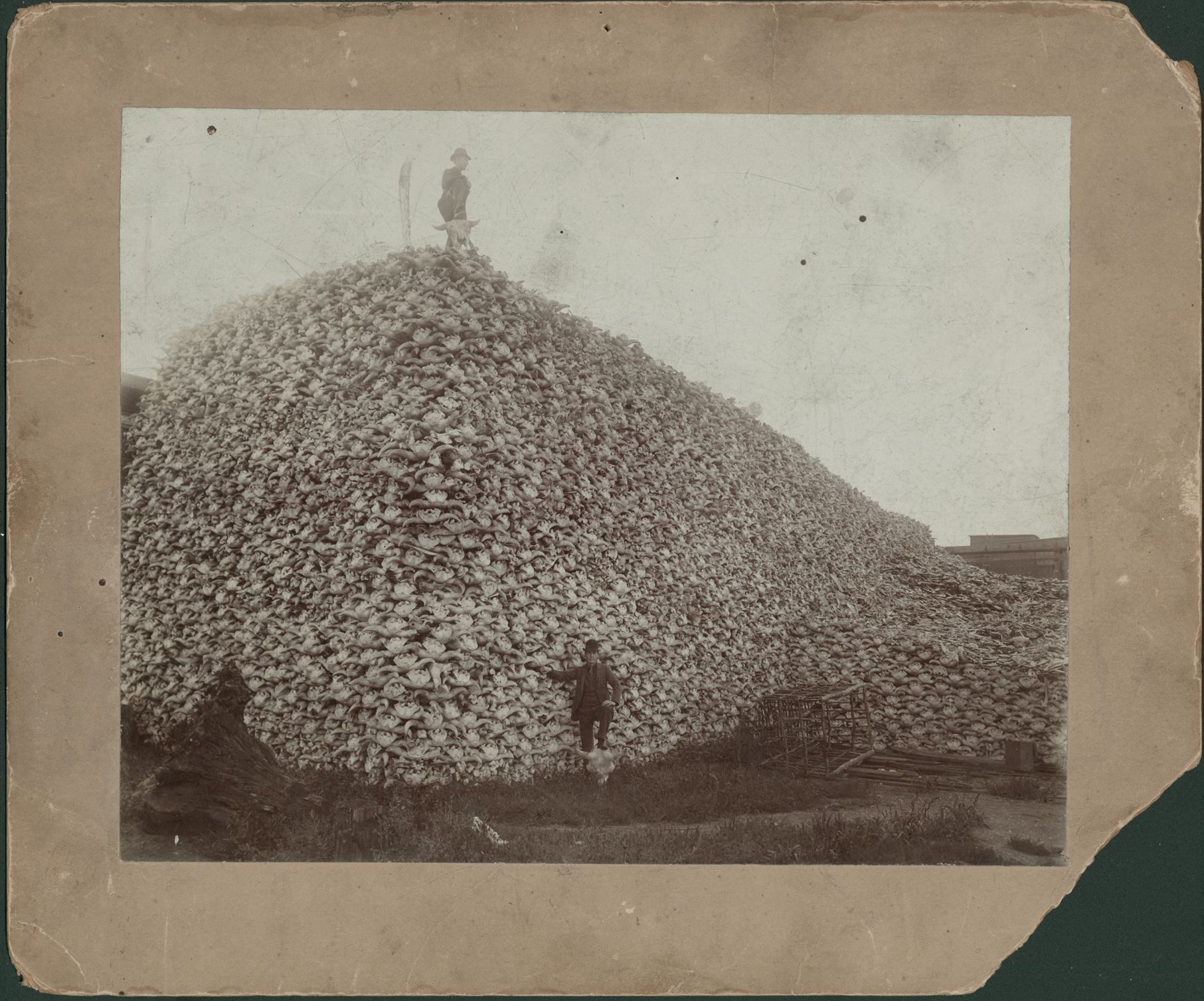

In addition to forced removals from traditional homelands, traditional food sources and food systems were destroyed by colonizing entities. In 1870, the demand for American buffalo hides for industrial machines on the east coast had driven the American buffalo to near extinction by 1900. “In just over a decade, the number of bison collapsed from 12-15 million to fewer than a thousand, representing one of the most dramatic examples of our ability to destroy the natural world,” states “The American Buffalo” film by Ken Burns. "The rapid disappearance of game from the former hunting grounds must operate largely in favor of our efforts to confine the Indians to smaller areas, and compel them to abandon their nomadic customs, and establish themselves in permanent homes,” states Columbus Delano in the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the year 1872. “So long as the game existed in abundance there was little disposition manifested to abandon the chase, even though Government bounty was dispensed in great abundance, affording them ample means of support. When the game shall have disappeared, we shall be well forward in the work in hand.”

Because of the interruptions to traditional food procurement processes and food insecurities within the new locations from the forced removals, many Native communities became dependent upon food rations from the U.S. government. To address the continued food insecurities for Native Americans on reservations, government-issued food commodities were introduced in 1977 through the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), administered by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). This program currently serves an average of 82,600 participants monthly.

Today, food insecurity remains a large issue for Native American communities nationwide, estimates ranging from 16% to 80%, where the baseline for the average American is 10.5%. “Food insecurity is a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food,” defined by the USDA. Food insecurity is directly linked to obesity and heart disease, resulting in higher utilization of healthcare. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents are 30% more likely—and adults are 50% more likely—to be obese than non-Hispanic white individuals. Native Americans with cardiovascular disease pass away before age 65 at a rate of 36%, compared to 31.5% of Black individuals and 14.7% of non-Hispanic White individuals. Related, there is currently a medical debt crisis for Native American communities. The Indian Health Service (IHS) has declined to pay medical bills for more than 500,000 patients, resulting in more than $2 billion in medical debt. In addition, according to the 2021 American Community Survey One-Year Estimates, Native Americans are the least likely to have health insurance (21.2% AI/AN, 19% Hispanic, 10.9% Black, 7.2% White).

Access to affordable, healthy, nutritious food options are limited in low-income communities, and purchasing power is influenced by whole communities, not just the individual. As many Native nations reside on remote locations and food deserts, the available foods are limited to those that hold longer shelf life, or those that are available at convenience stores and gas stations due to the distance of full grocery store access. However, access is not the only solution to a problem created through decades of systemically imposed restrictions on indigenous diets. Food choice is influenced by many factors from biochemical and physiological to psychological and social. Many of these are through cultural experiences in childhood that are internalized at the subconsious level.

While financial education alone may not address this multi-layered, multi-systemic issue that is contributing to health and financial disparities for Native Americans, there is a correlation between financial knowledge and weathering hardships from food insecurities. Moreover, trauma-informed financial education has been shown to address several nuances of finances, including social, behavioral, and emotional issues associated with food insecurities.

Discussion- West/Tobacco/Maintenance

Native American communities survived from the land for centuries and many families had ancestors that lived to be centenarians. “My grandmother used to talk about how the people two or three generations before her would live to be like 100, 110 years old. We've got pictures of my great-grandfather, this guy named Peter, who is out treaty fishing in the 1900’s. He was 95…105 years old…something like that. He seemed like a pretty robust dude,” shares Professor Matthew Fletcher (Anishinaabe) Harry Burns Hutchins Collegiate Professor of Law and Professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan. “We asked my grandmother about that. She said, ‘You know, people just ate what they found in the earth. They grew their own food. They didn't go out to eat much. They didn't have any money to do that. So, you ended up eating a lot of weird things like skunks and possums, really gamey stuff. It was gross, but it was really healthy. And so people lived a lot longer, you know, if they made it that far… And that was my grandmother’s explanation for it.”

Through the process of colonization, Native American communities were relocated off traditional homelands and exchanged land for promises from the government through treaties. “Food commodities are there because it was part of the contractual agreements that we made with the government that they would and we would give them our land,” shares Paul McHorse (Taos Pueblo), Owner and Senior Planner of First Nations Eagle. “So, contractually, it's something that we must continue to have access to. And it is something that our ancestors advocated for so that we would have sustenance to survive because our old meat sources were no longer available to us” (P. McHorse, interview, July 17, 2023).

“When we look at the three main consorts that the federal government says of taking our land, ‘we will provide education, we will provide food, we will provide housing’, every single one of those measures from the time colonization began has been inadequate. And, in my mind, has been put forth as a measure to hurt our communities. If this was provided to any other community other than a marginalized community, so take this out on a racial standpoint, privileged and white individuals would never stand for this nor would the federal government even dream about providing such unhealthy food in such low measures. So, this really is still a measure of the prejudice, ineptness, and lack of treaty trust responsibilities of the federal government,” states Chrystel Cornelius (Ojibwe, Oneida), CEO of Oweesta Corporation.

“I think it's still part of that structural violence that happens. That they're not meant to nourish our bodies, they're not meant to help us in any way, right? They are intentionally, and have been intentionally, used as violence, as an act of violence on Indian bodies,” states Dr. Vanessa Esquivido (Nor Rel Muk Wintu, Hupa, Xicana). “So they know that we are in a place where we will accept these things because it's free food and we have food scarcity. And I think that behaviorally, we know that our—a lot of our ancestors, when they first got to the reservations, had to live off these.”

“I think it was a big disruptor to our communities. When I learn about commodity food and the forced use of it in our communities,” adds Jaime Gloshay (Dine, Apache, Kiowa), Co-Founder of Native Women Lead. “I think about people being put into landlocked reservation systems. I think about people being corralled and controlled and forced to adopt a diet that wasn’t our own. And now that I see the huge health inequities that exist and the health issues that exist in our communities as it relates to like heart disease or diabetes or any high blood pressure stroke, and even our bodies adopting to Western foods, I think it's had a really negative influence.”

“So, I know commodities were very influential in just creating fry bread, which is like a staple now. But health-wise, it's not healthy. So yeah, it has really changed, I think, our culture and our quality of food. And even it’s disconnected a lot of our connection to our ancestral foods and medicines and land,” states Jaime Gloshay (Dine, Apache, Kiowa).

Chrystel Cornelius (Ojibwe, Oneida) shared the inception of fry bread. It was created out of necessity for survival. The ingredients would arrive spoiled, the lard would be rancid and the flour filled with bugs and weevils. Native American ancestors learned that boiling the lard would turn it from rancid and the process of frying would kill the bacteria. They would leave in the bugs because it was a source of protein. Fry bread is one of the most known Native American dishes across the nation.

Dawn LeBeau (Lakota) reflects on growing up with commodity foods and knowing as an adult that the foods are not nourishing. “But what I see in my community and within my family is a lot of folks are purchasing, like, the very high processed foods and there needs to be more education around what our food system actually looked like growing up, why we harvested certain types of veggies and grew our own foods and processed our own beef. It really is like the biggest conversation right now because our communities are suffering from different health factors that we could potentially eliminate or decrease based on what type of foods that we let into our bodies.” She goes on to emphasize the importance of consumer education and balancing the cost of higher priced foods in the present versus the cost of poor health in the future. Where processed foods might be more appealing, education on the health trade off can empower community members to make the best decisions.

“But if we have governments that understand and actually put people in place who have compassion and love and are savvy and educated, then they can help lift up the people, their citizens, because that's really their job,” imparts Paul McHorse (Taos Pueblo). “And, they can lift them up to the point where commodities are a thing of the past. And looking into the future is having elk, having buffalo, having deer, having good meats that are free range, that our bodies are built for. Our bodies aren't built for commodities and highly processed foods. They're built for fast and famine. We're built for ceremony. We're built for seeing life as... as a way to see the beauty that was created for us and to live in harmony with that beauty” (P. McHorse, interview, July 17, 2023).

Wisdom- North/Sage/Conclusion

In conclusion, Native American communities have been forced in disconnection to culturally-based foods and harvesting practices through ancestral land displacement and supplemented for survival on heavily processed government rations and commodity foods, leading to health disparities and cultural normalization of non-traditional foods. Trauma-informed, holistic financial education can be integral in Native American communities reclaiming autonomy and sovereignty in traditional and accessible food systems.

Disclaimer- Mother Earth

There are 574 Federally Recognized tribes and hundreds of unrecognized tribes in the United States, each with a unique colonization story that has influenced their community members’ and descendants’ interactions with the mainstream financial system. These articles are intended to explain a generalized Native experience and support a journey of positive change in relation to Native American, Hawaiian Native, and Alaskan Native communities.

About the Weaver- The Spirit Within

Boozhoo, Migizi ‘ikwe Nindigoo. Stephanie Cote Nindizhinikaaz. Grand Traverse Band Odawa minwaa Ojibwe Nindibendaagoz. Maengun Nidodem.

Hello, spirits know me as Eagle woman. I am called Stephanie Cote. I am from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. I am from the Wolf clan.

Stephanie Cote descends from a lineage of basket weavers. Honoring her ancestry, these articles are woven from common Native knowledge, accessible online articles, and the wisdom imparted by Native peers and elders to support hypotheses developed from the intersectionality of Native American experience and financial education. She is Odawa and Potawatomi from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians from Northern Michigan and a Senior Program Officer at Oweesta Corporation leading the Financial Education and Asset Building Department.