Abstract- Father Sky

The final piece of the series focusing on the intersection of financial education and the Native American experience, this article discusses models of economic development that cultivate financially diverse and thriving Native American communities. When integrated with appropriate resources, financial education can be an integral tool in uplifting community members and whole communities. This article also highlights the ways in which allied individuals and agencies can best support financial education and economic development efforts in Native American communities.

Prayer, Song, and Introduction- East/Sweetgrass/Beginning

Gimikwenimigo giizis ezhi-zaagiiaasigeyan (Anishinaabe/English)

We remember you sun how you shine

Gimikwenimigo dibiki-giizis baabaabii’oyan

We remember you moon waiting

Mikwendaagozidaa apane gosha

We should all remember always

Mikwendaagozidaa apane gosha

We should all remember always

Gimikwenimigom aanikoobijiganag

We remember the connected ancestors

Gimikwenimigom inawemaaganag

We remember all our relatives

Mikwendaagozidaa apane gosha

We should all remember always

Mikwendaagozidaa apane gosha

We should all remember always

Gitchi-manadoo, Creator, chii miigwetch, many thanks, for the strength of our Tribal Nations and the continued perseverance of our community members to fight for the rights and freedoms of our relations existing today and seven generations in the future. Thank you for answering the prayers of our ancestors that we may carry on our Native traditions and spirituality with honor and in reverence of your blessings. Chii Miigwetch, Many Thanks (Anishinaabemowin/English).

This is one piece of a seven-part series unpacking the complexities surrounding financial education, including financial wellbeing, for Native American communities, utilizing interviews from prominent Native American individuals across the financial education sector and accessible literature. Together, these seven pieces create a snapshot of this landscape.

This final article will discuss many facets of the National Endowment for Financial Education’s Personal Finance Ecosystem, the visual model of the interconnected concepts that influence an individual’s financial well-being. Because this article examines the community economy level and its impact on individual financial well-being, the concepts from the Personal Finance Ecosystem influencing the individual’s financial well-being include Foundational Factors such as family and culture, as well as socioeconomics and geography; Financial Knowledge & Access including access and inclusion; and Financial Actions and Outcomes involving mindset and available choice sets.

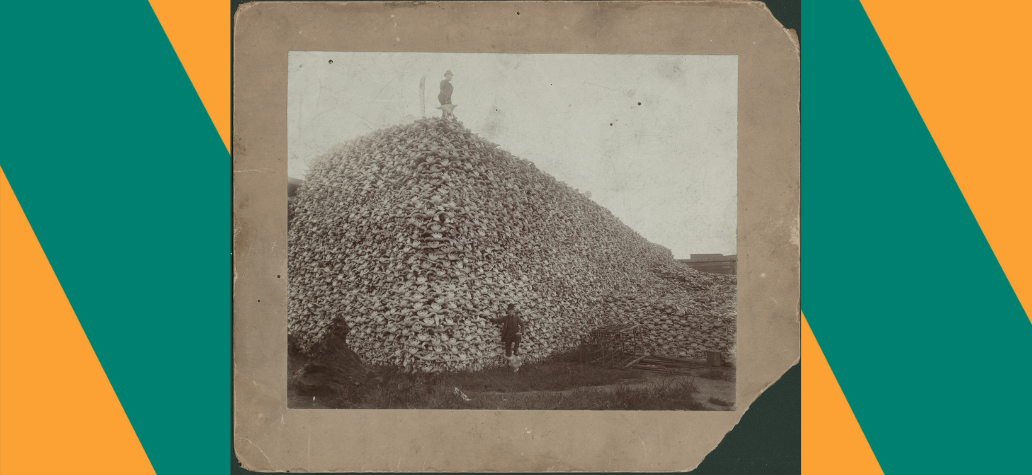

History- South/Cedar/Growth

Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska: A Case Study for Economic Advancement

The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska is one of two Ho-Chunk tribes that are federally recognized in the United States. The reservation land was established in Thurston County and Dixon County in 1865 and is currently 112,990 acres, with 27,637 held in tribal trust. In 1936, the tribal government was established. Similar to many tribes, much of their land in the early 1900’s had been turned into tribal trust land, meaning it would not be collateralized. The reservation is in the northeastern corner of Nebraska and crosses the Missouri River into the western side Iowa with a total population of 2,737 individuals on and off-reservation trust land, according to the 2020 U.S. Census. The central city within the reservation—Winnebago, Nebraska—is about 20 miles south of Sioux City, Iowa (population: 85,757) and 81.7 miles north of Omaha, Nebraska (population: 486,051).

In December 2023, Ho-Chunk Incorporated, a Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska corporation, released a comprehensive study analyzing the social and economic impacts within the community from 1990-2022. These insights, along with additional resources, help illustrate the economic advancements the tribe had made to establish a self-sufficient economy on the reservation. As described in the article, “The Origin Story: Manifest Destiny’s Creation of Economic Deserts and the Devastation of the Subsistence Economy,” Native American tribes are recognized as separate legal governing bodies over their communities, much like that of states. By the 1970’s and 1980’s, Native American tribes were utilizing gaming models to generate revenue to support the tribal economies. This was a unique form of income for tribal communities because many states had imposed restrictions and prohibitions on gambling and gaming. In the late 1970’s, the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska had opened their first gaming operation in the form of a bingo hall to generate capital for the tribe. The Cabazon Decision of 1987 granted tribes legal access to operating gaming establishments without being subject to criminal sanctions if the state the establishment was in allowed some form of gambling to charitable organizations, state lotteries, etc. The Indian Gaming Act of 1988 was passed by United States Congress to regulate gaming on Tribal lands. The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska turned their bingo hall into a Class III, Vegas-style casino called WinnaVegas Casino Resort. The primary goals of the revenue from this resort were to enhance Winnebago culture by revitalizing language and culture, address alcoholism and health issues within the community, protect tribal sovereignty, and create a self-sufficient economy. Tribal Chairman Ruben Snake and other leaders developed the 20-year plan of attaining economic self-sufficiency by 2000.

In 1994, the charter to establish Ho-Chunk Incorporated (Ho-Chunk, Inc.) was passed. This company was established with a dual mission of creating jobs within the community and to help the tribe achieve the goal of economic self-sufficiency. Between 1994 and 2018, the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska generated a multi-institutional tribe:

- 1996: Tribal Housing Authority, offering adequate and safe housing to enrolled tribal members on the reservation and emergency home repairs for members without the resources of income to address the needs.

- 1998: The Little Priest Tribal College, a Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska chartered school, providing two-year associates degrees and certifications, preparing students to transfer, if desired, to complete a four-year degree.

- 2000: Ho-Chunk Community Development Corporation (HCCDC), a 501c3 nonprofit with a mission to enhance economic, education, and social opportunities for tribal members.

- 2001: Housing Down Payment Fund, providing a significant portion of a standard down payment for a new homeowner, including educational courses.

- 2004: Ho-Chunk Village, a real estate development, including a farmers market, café, elder housing, retail spaces, manufacturing businesses, a public park, and a residential area with over 110 housing units featuring single family homes, multi-family rentals, and live-work units.

- 2007: Winnebago Community Development Fund, a tribally chartered nonprofit organization utilizing tax proceed funds to support community activities and infrastructure through matching fund grants.

- 2014: Educare Winnebago, an early childhood development institution preserving culture and tradition through education in the Ho-Chunk language to 175 children from birth to age five, providing after-school tutoring for K-3 grades, and hosting community college classes.

- 2016: Ho-Chunk Community Capital Corporation (HCCC) Community Development Financial Institution, supporting families and small businesses with financial services and loan capital.

- 2018: Twelve Clans Unity Hospital and Pharmacy, a comprehensive hospital serving 10,000 Native Americans on the reservation and in surrounding communities.

Ho-Chunk, Inc. has contributed over $43.7 million to the tribe since 1994, giving away more than $275,000 in charitable donations, and generating 3,525 jobs in 2022, supported by Winnebago operations. There has been a 100% increase in Native Americans enrolled at Winnebago High School since 2000 and 302% increase in adults over 25 years old with degrees. Similarly, there was a 12% increase in homeownership from 1990-2022. Highlighted statistics from the past three decades include a 37% increase in per capita income for tribal members, a 5% drop in unemployment, and a 4% increase in labor force participation.

Twelve Clans Unity Hospital of Winnebago

In addition, Ho-Chunk, Inc. has been participating in government contracting through the Small Business Administration 8(a) Business Development Program for minority and disadvantaged businesses. In a written testimony for the House Small Business Committee Subcommittee on Contracting & Infrastructure, Ho-Chunk, Inc. commended government contracting for its contributions to the advancement of education, healthcare, public works, and other community needs.

In an effort to mitigate predatory lending through border-town car sales, Ho-Chunk, Inc. developed Rez Cars to sell cars at an appropriate price and rate to help community members on their credit journey and in their home purchasing endeavors.

Similarly, Ho-Chunk, Inc. pursued revitalizing Winnebago farming by investing over $1.1 million in agricultural operations through Ho-Chunk Farms. With Ho-Chunk Farms, the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska is able to participate in several U.S. Department of Agriculture programs, create long-term sustainable food sovereignty efforts, and increase the workforce in the agriculture industry.

In an effort to mitigate predatory lending through border-town car sales, Ho-Chunk, Inc. developed Rez Cars to sell cars at an appropriate price and rate to help community members on their credit journey and in their home purchasing endeavors. Similarly, Ho-Chunk, Inc. pursued revitalizing Winnebago farming by investing over $1.1 million in agricultural operations through Ho-Chunk Farms. With Ho-Chunk Farms, the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska is able to participate in several U.S. Department of Agriculture programs, create long-term sustainable food sovereignty efforts, and increase the workforce in the agriculture industry.

The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska has financial education options available from multiple sources. Ho-Chunk Community Capital offers financial literacy, small business development and homeownership preparation courses that co-exist alongside their loan offerings. The Nebraska Financial Literacy Act requires personal finance courses as a requirement for high school graduation, as well as financial literacy instruction in grades K-8. Currently, Winnebago High School is teaching, “The More You Learn, The More You Earn.” Little Priest Tribal College regularly offers community courses that include financial education topics. In Spring 2024, “Financial Market Basics” and “How to Save” were courses taught and Fall 2023 offered “Household Finances.”

Discussion- West/Tobacco/Maintenance

Members of the Winnebago Indian Tribes dance team, perform authentic Native American ceremonial dances at the Lied Activity Center in Bellevue, Neb., on Nov. 15, 2006. The tribal dance performance was the highlight of the culture fair events, held as part of Native American Heritage Observance month.

As Lance Morgan (Ho-Chunk), president and CEO of Ho-Chunk Incorporated, states, “You can’t just wave your magic wand with some economic policy and everything sort of shifts. It really comes down to regular education, financial education opportunities, providing quality homes, fixing people’s credit, and access to capital.” He goes on to say that by providing this support, tribes can be a catalyst for breaking generational financial trauma. An example he gives is the Ho-Chunk Downpayment Assistance Program. By assisting one person in fixing their credit and providing much of the capital needed for the initial purchase of a home that many young people are unable to save, they break the cycle of relying on tribal housing and the cycle of trauma and stigmas associated with tribal housing (interview, Lance Morgan, May 24, 2023).

Onna LeBeau (Omaha), director of the Office of Indian Economic Development, shares her perspective as a member of the neighboring tribal community, Omaha Tribe of Nebraska, on the southern border of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska reservation.

She mentions that it is a stark contrast in comparison with her community. She saw the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska start by investing in their casino, and immediately taking the revenue and investing it into more community development opportunities. When traveling back home, she would go through Winnebago and see the progress they would make throughout the years.

She saw the way they were investing in every level of the community. Onna LeBeau reveals that the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska had built up their individual community members by first starting with financial education to get them ready for homeownership. Once they had established homeownership, they were able to start their own businesses that contributed back to the local economy. She states, “And then so many of their tax dollars were going back into the community via the school, new hospital, new roads, new homes, just a whole new village. And, of course, that created more jobs. Then people buying their homes started demonstrating that pride in what they had acquired for themselves.” She concludes, “That is how I see a thriving community, where it’s truly about helping the community and not necessarily sharing money, but just sharing of oneself to be able to support each other.” (interview, Onna LeBeau, May 15, 2023)

Christopher Cote (Anishinaabe), business development impact manager at First American Capital Corporation conveys that financial education is key to creating community-wide financial well-being. As discussed in the previous article, “Success of Grassroots, Native-led Financial Education,” financial management is a western concept with a unique language that needs to be integrated into various American communities. He sees within the communities he serves that access to financial resources needs to be paired with appropriate education of those resources to truly be effective tools in individual and community economic growth (interview, July 13, 2023). “Financial wellbeing is really seen now in a holistic way,” imparts Jaime Gloshay (Dine, Apache, Kiowa), co-founder of Native Women Lead. “How finance can be used as a tool to drive social change, and also as a way to economically empower people toward greater agency, self-determination, autonomy, and being able to live not only in safety, but in abundance.” She goes on to discuss the relationship of reciprocity within a community, taking care of each other in balance, honoring our cultural and social responsibilities (interview, July 20, 2023). Dr. Christy Finsel (Osage), executive director of the Oklahoma Native Asset Coalition, reveals that there are reciprocal relationships between stakeholders in building a thriving Native ecosystem. This model includes collaboration between the nonprofit sector, tribal governments and corresponding departments, and community development financial institutions. Ideally, “parties that are working together and have equitable access to funding and are thriving and functioning.” (interview, May 21, 2023).

“We hold the blood of our ancestors, and we really are, in my mind, the manifestation and dreams that our ancestors prayed for,” Chrystel Cornelius (Ojibwe,Oneida), CEO of Oweesta Corporation, discloses. “Financial wellbeing on my part too is when we look at that seventh generation, what are we building for them? Did we do something to make sure that they can still be Native?” (interview, July 12, 2023) Many of the interviewees had expressed that their image of a thriving Native American community would embody the qualities and characteristics that have been fostered over the past three decades in the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska community. Their practices are rooted in the seven-generation teachings and creating a ripple effect of sustainability throughout.

Call to Action: Recommendations for Supporting Economic Growth in Native Communities

Financially Support Tribal Sovereignty

Because tribes and tribal communities have been limited in accessing financial resources from traditional banking systems, whether that be from physical structures providing capital, home loans on restricted lands, or small business capital on reservations, the best way to support tribes is to create access points to this capital. Access points could include, but are not limited to, philanthropic support to tribally-run nonprofits, donating to Native nonprofit organizations that support tribes and tribal nonprofits (such as NDN Collective, First Nations Development Institute, Native American Rights Fund, Oweesta Corporation, and many more), or supporting Native-owned or tribally-owned businesses (such as SisterSky, Eighth Generation, Sage and Oats, and many, many more). Supporters are uplifting the sovereign rights of Native Americans by directly funding Native businesses and organizations instead of dictating to the community what an outside perspective might view as what the community needs. This is articulated in Edgar Villanueva’s book "Decolonizing Wealth" where many times in philanthropy the intention is for the greater good, however, the outcomes are not addressing systemic change that needs to happen and are merely a surface-level fix. Additionally, while any funding is better than no funding, if we want to see long-term change, we need long-term capital opportunities. An example would be long-term, low-cost capital for Native CDFIs that can accommodate 20- and 30-year mortgages to address their tribal housing crises.

Advocating for Financial Education Requirements in All Schools

The interviewees all stressed the importance of financial education starting early for all children. Because financial education has been lacking in formal education settings for generations, this information is often not taught in the home and needs to be taught in schools. Advocating for a national policy on financial education requirements in public schools would benefit not only Native American children, but all children across the nation. Currently, only 25 states require financial literacy to be taught in high school. One class in high school is not sufficient to carry throughout adulthood. Arguably, financial literacy should be taught alongside any form of literacy, and equivalent to a fluent level of comprehension in a language course. Moreover, if four years studying a foreign language is not enough to meet proficiency standards, one semester of financial literacy would not be enough for students to understand all the intricacies of American financial practices. The Council for Economic Education identified National Standards for Personal Financial Education to include earning income, spending, saving, investing, managing credit, and managing risk, all of which can be adapted to K-12 education levels. The best practice is to have a culturally relevant financial education, on the other hand, similar to financially supporting tribes, any financial education is better than no financial education.

Support Policy and Advocacy Efforts

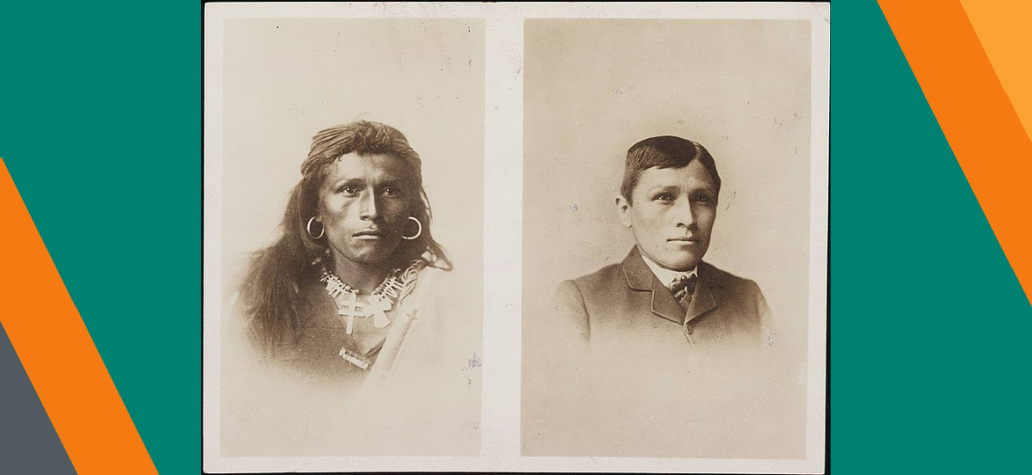

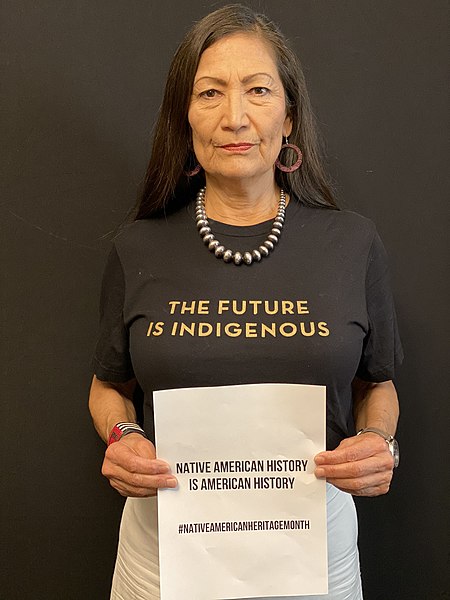

By supporting leaders that have the best intention for Native American rights and uplifting Tribal sovereignty, we can ensure that public policies will not be detrimental to our Native American communities. Conversely, leaders that are openly against supporting Native American rights or Tribal sovereignty have negatively impacted tribal communities, disregarded or revoked treaty rights, adopted policies around natural resource extraction that put the health and safety of tribal communities at risk, and actively suppressed Indigenous entitlement to preserving culture. In addition, supporting policy advocacy organizations and political representatives with lived cultural experience in Native communities is an important consideration in cultivating a greater nation of equal representation of our communities. For generations, there has been a lack of Native American representation in places that were dictating the Native story or making important decisions for Native Nations. Having representation with lived experience is irreplicable and invaluable.

Wisdom- North/Sage/Conclusion

In conclusion, financial wellbeing for Native American communities includes financial education at all stages of life, a reciprocal relationship between community stakeholders and members generating positive economic growth, and a seven-generation mindset in community development efforts. With holistic support from allied nonprofits and philanthropic organizations as well as the government and individuals, Native Nations can obtain economic self-sufficiency and prepare for the sustainability and prosperity seven generations from today.

Disclaimer- Mother Earth

There are 574 Federally Recognized tribes and hundreds of unrecognized tribes in the United States, each with a unique colonization story that has influenced their community members’ and descendants’ interactions with the mainstream financial system. These articles are intended to explain a generalized Native experience and support a journey of positive change in relation to Native American, Hawaiian Native, and Alaskan Native communities.

About the Weaver- The Spirit Within

Boozhoo, Migizi ‘ikwe Nindigoo. Stephanie Cote Nindizhinikaaz. Grand Traverse Band Odawa minwaa Ojibwe Nindibendaagoz. Maengun Nidodem.

Hello, spirits know me as Eagle Woman. I am called Stephanie Cote. I am from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. I am from the Wolf clan.

Stephanie Cote descends from a lineage of basket weavers.

Deb Haaland, 54th United States Secretary of the Interior, celebrating Native American Heritage Month in 2019.